Toná

Coproduced by Madrid Autum Festival

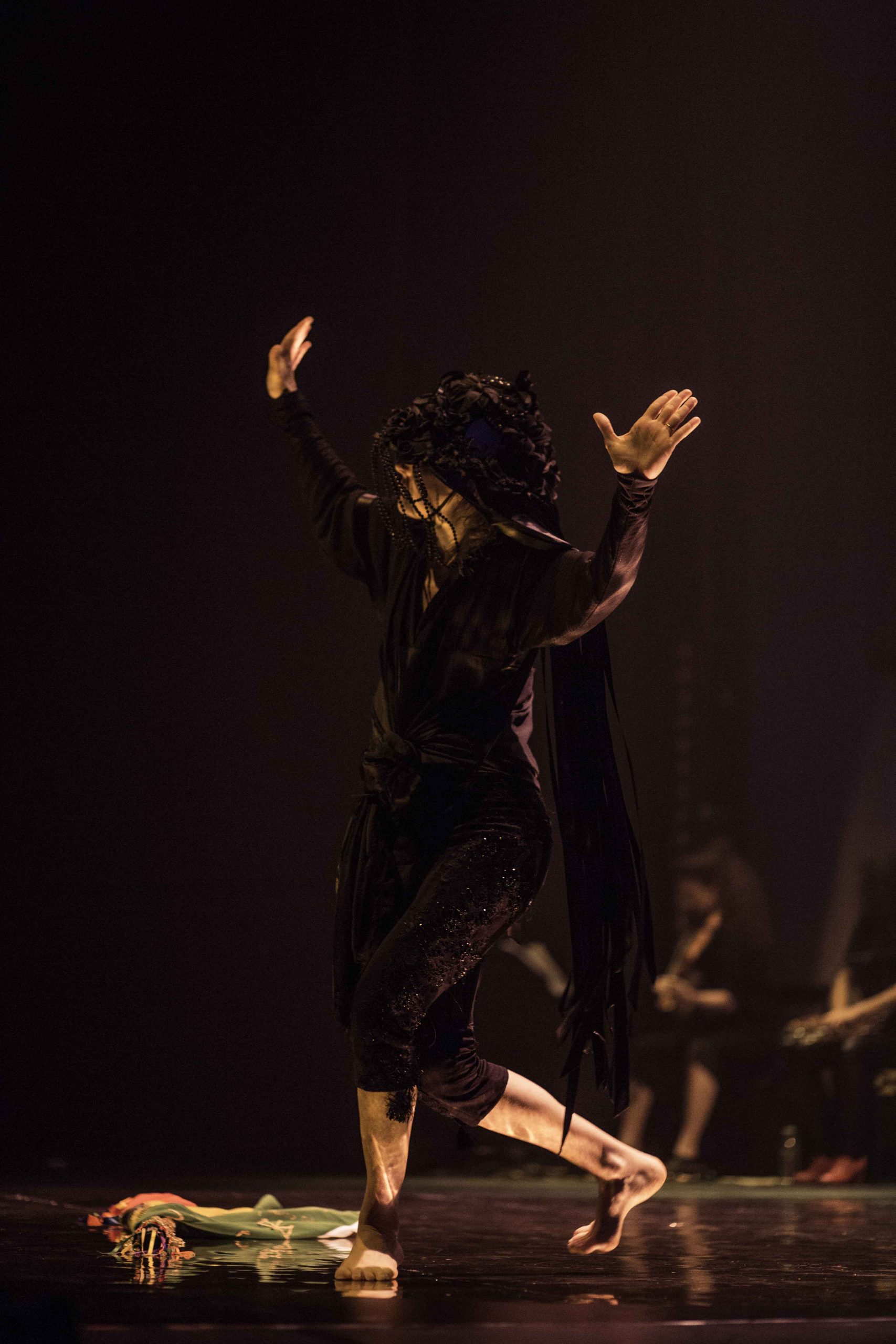

Toná is born from the need to embody a broad identity, that does not strive to have its essence defined, linked organically to collective memory and popular imaginaries with all the conflicts that entails. A poetry that transmits flesh, the vital pulse, full of rage and joy, as well as of prejudices and superstitions. An ancestral and fertile pain that, from childhood onwards, gradually makes us what we are.

An identity as luminous as it is dark, which cannot be reduced to the metrics of productivity and consumption, a physical outpouring that refuses to be inscribed by the inertia of opinion and its euphoria, posing, protocol.

A body reconciled with its vital forces, interwoven with illness, old age, death and that brazenly embroils itself with symbols so that they may be sullied, trod upon, renamed, whilst shouting: they are ours, they belong to us.

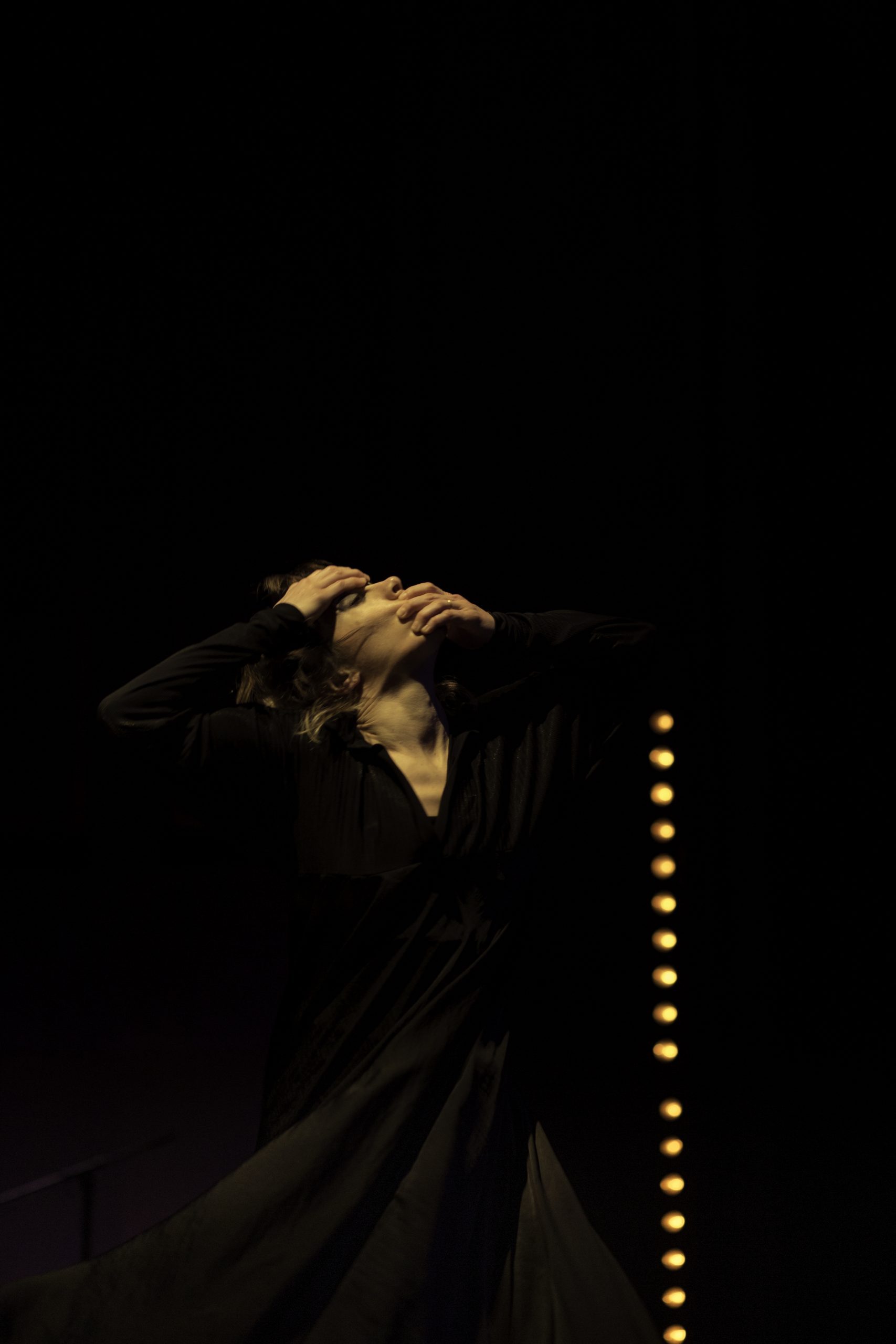

A body that doesn’t choose between believing and suspecting: faith and nihilism as brothers in arms, repeating to each other that loving is to have the keys to heaven and realise that heaven is empty.

“Shame is the feeling that shall save Humanity.” It won’t be love, but rather shame.

A pain that is ancient and fertile: flesh, bodies. Identity is the mystery that hides in every body and emerges from the intimate reconciliation with shame.

I look for dance in bodies, its folklore, its wound, not the virtuous dance of trained bodies, but dance— human dignity summoning us, daring to stamp the floor with the force of shame. The most beautiful anger, the most open wound.

DIRECTOR, DRAMATURGY, PERFORMER, & CHOREOGRAPHY

Luz Arcas

SCENIC AND CHOREOGRAPHY ASSISTANT

Abraham Gragera

DRAMATURGY ASSISTANT

Rafael SM Paniagua

MUSIC DIRECTION AND COMPOSITION

Luz Prado

ARTISTIC ASSISTANT

Nino Laisné

DANCE

Luz Arcas

VIOLIN & ELECTRONIC

Luz Prado

VOICE, CLAPS & PERCUSSION

Lola Dolores

CUSTOME DEIGN

Carmen 17

FLAG DESIGN

Isa Soto

MAESTRA DE BANDERA

Paula “La Albardonera”

SCENOGRAPHIC ASSISTANT

José Manuel Chávez

DISEÑO Y CONFECCIÓN DE LAZOS Y FLORES

Elena González-Aurioles

PHOTOGRAPHY AND VIDEO

Virginia Rota

SOUND DESIGN

Pablo Contreras

LIGHTING DESIGN

Jorge Colomer

EXECUTIVE PRODUCTION

Fernando Jariego

PRODUCTION DESIGN AND COORDINATION

Alex Foulkes and Alberto Núñez

TOUR MANAGER

Andrea Méndez Criado (Spectare)

GRAPHIC DESIGN

María Peinado

COMMUNITY MANAGER

Carlos González

“la búsqueda de un nuevo lenguaje , capaz de amalgamar danza contemporánea y flamenco, la búsqueda virtuosa de una bailarina y coreógrafa que habla con cada fragmento de su cuerpo y que nos sorprende con los simbolismos sacados del mundo taurino y de las fiestas españolas”

“de hecho se podría concebir un espectáculo sólo con el movimiento de los pies de Luz Arcas , que son el núcleo, el quid y la espina dorsal de su partitura física , de sus danzas atávicas, de su estar en escenario”

“Una hora de pura energía y catarsis en la que la artista baila la muerte incorporándola en una atmósfera folclórica”

“La coreógrafa -a veces con tintes preciosamente gamberros- llena de otro fervor el escenario. Una vuelta a su infancia hoy reinterpretada que llena de festividad y del propio espíritu del folclore. Ella habla de la muerte con respeto porque respeta el miedo antiguo, pero aquí Arcas la celebra. Está celebrando la muerte. Celebra el folclore de la muerte como celebra la vida, porque ella es la celebración de lo negro, de la muerte, del llanto, de la virgen. Ella es otra virgen. La campesina con sentido de comunidad. La mujer tribal. La niña fotogénica del pueblo indígena que deshoja nuestras máscaras de cemento y de alquitrán varado.